This old structure at Half Acre was once a tavern/inn on the Seneca Turnpike (also call the Genesee Road) two miles west of Auburn, N.Y. It stood on the north side of the road. Built during the heyday of the stagecoach era, it was originally operated by Henry Ramsay in the 1820s or before. Later it was operated by Henry who in turn sold it to Diodorus Westover in 1856. Upon his death in 1864 his wife, Betsey, and daughter, Susan May, operated it. The local post office was located here "conveniently" next to the bar. The dining room in the old days could seat 40. There was a ballroom on he second floor. Many social events were held here. Upon Mrs. Westover's death in 1908 it was razed to allow expansion of the local cemetery. Two other taverns still stand at the corner as private homes.

Getting There 'By Stages'

The old stagecoach came into town with a flourish amid the clatter of galloping horses and sounding horn - its round body swung on leather strap thorough-braces; its passengers tossed about like dice in a box.

The gallant driver pulled on the reins and the four steaming horses halted in front of the inn. Shouting boys swinging from the “boot,” at the rear of the coach where baggage was stowed, fell off in a cloud of dust. After whirling up to the “stoop,” the traces of the horses were unhooked and the exhausted animals were led around to the stable to their familiar stalls. Usually, stagecoaches in this part of the country employed four-horse teams. The horses in front were the leaders and the rear two, the wheelers.

The stage driver himself, donned in a great-coat and buckskin gloves, strolled into the inn with his traveled air. He was a welcome figure in every village along the old turnpike which depended on his arrival for the mail and the latest news from the outside world. Gazed upon with awe by the boys, he was worshipped as a sort of romantic hero, who never worked, but drove his galloping horses back and forth through a perpetual holiday.

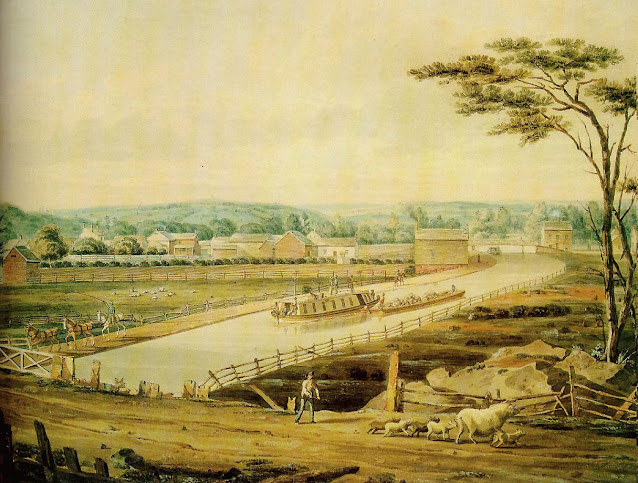

Soon the stable boys trotted out a fresh team and in a few moments the passengers reclaimed their seats. The driver mounted his seat, called the “box,” slung the mail sack beneath him, sounded his bugle, and with a crack of the whip over the tops of horses’ heads, he galloped off down the dusty road. This was the stagecoach era as it existed in upstate New York for a more than half a century. From 1790 until the completion of the network of railroads across the state in the early 1840s the stagecoach reigned as the supreme mode of public conveyance, supplementing the Erie Canal packet boats.

During this period the stage proprietors on the great western routes aligned, or associated themselves; working in close agreement to control the road to keep a tight rein on competition. This syndicate, as it might be called today, was known as the “Old Line Mail.” People such as Asa Sprague, Aaron Thorpe, Jason Parker, Isaac and John M. Sherwood had a virtual monopoly on the stage business across the state for nearly a half century. This conglomerate was a well-oiled machine that required vigilance and tight communication to keep the business moving and satisfy the demands of an impatient and exacting traveling public. It was highly-organized, employing hundreds of agents, drivers, station-keepers, runners, clerks, mechanics, blacksmiths and tavern keepers.

The “Old Line” proprietors proved themselves equal to the task. Their commanding energy in moving with regularity and order such a mass of human and animal elements was proverbial, considering the wretched roads and turnpikes they had to contend with, which varied with the seasons from bad to worse. During winter and spring the roads could be a terror to timid passengers, occasionally becoming impassable. Now and then the teams would become mired in the mud and passengers would assist in lifting the coach out of a mud hole. In winter, the coaches were mounted on runners, or as they used to say, "a set of bobs."

Long stretches of road through swamps were bridged on stretches of corduroy, formed by cutting down the adjacent timber, trimming off branches and placing the logs side-by-side across the right of way. Under such rough conditions, timid travelers would stop over at a convenient wayside tavern for the night and rest until another stage came along. Such a trip from Albany to Buffalo frequently required nearly a week in the very early days. Although many hardships were encountered in traveling by stage, such a journey was not entirely void of pleasures. There were deep forests of towering hemlocks and pine trees. Here and there a little clearing appeared where a settler and his family had built a log house, feebly attempting to cultivate the rutted soil. The scenery was varied and interesting. The passengers generally were sociable, and many warm and lasting friendships were formed in the “old coach and four.”

Paralleling the Great Western Turnpike which ran from Albany to Manlius, to the north was “The Great Genesee Road” which ultimately became the Seneca Turnpike. It was much more of an extensive system of roads than the “Cherry Valley.” The main route was from Utica to Canandaigua. At Chittenango, a branch diverged and passed through Manlius, Jamesville, Marcellus and Skaneateles, and on to Auburn, where it rejoined the north or main branch (today’s Route 5) which passed through Syracuse, Camillus and Elbridge. Another branch diverged at Sennett and headed cross country to Cayuga, where it rejoined the main branch to form a single road again through Seneca Falls, to Canandaigua.

Several coaches ran regularly over these routes daily, besides “extras,” which ran frequently to meet travel demands. The “motive power” was first-quality horse-flesh, athletic, sure-footed and strong. A coach weighed 2,200 pounds, and carried 11 passengers with baggage. Each horse had a name, and, when called upon, responded to the driver’s commands. The driver’s whip was composed of a stalk four or five feet long, to which was attached a lash 10 to 12 feet long. At the end was a nicely braided silk “cracker.” It was a great piece of dexterity to hold the reins of four horses, and so wield the whip as to give a smart crack with it; or in coming down the hills, to crack the whip and blow the horn, holding the four reins in one hand and the horn in the other, with the horses under full gallop. It is said it was an inspiring sight.

Stage drivers were a daring lot, but very energetic and faithful to the performance of their duties. Accidents were few and far between. Hiram Reed of Marcellus recalled that as a boy he and a friend commuted to Skaneateles on the Auburn stage. One day they climbed up with the driver, which was not usually allowed. As they descended a steep hill between Marcellus and Skaneateles, one of the pole straps leading from the front end of the reach to the collars of the wheel horses, broke.

“Hold on boys!” the driver shouted, and at once laid the whip to his horses. They galloped headlong down the steep hill in perfect safety. The driver was able to steer the coach to safety by controling the slack of the reach, or pole to which the wiffletrees were connected. This was also referred to as a thill. The was the last time the boys rode with the driver.

Horses were changed every 10 miles, but a driver would typically run 30 to 40 miles. If for some reason he was in a hurry and the roads were good, he could make 10 miles in less than an hour. But the Old Line proprietors did not encourage racing, even though it frequently occurred when there was a competitive stage line trying to make inroads.

The stage fare was five cents per mile. The ‘way-bill,’ which every driver carried, was another feature of the road. If a person in Auburn was going to Albany he would go to the stage office and the agent would register him. By this system the driver was saved the trouble of handling the fares. Colonel Sherwood had the contracts for carrying the mails over a large section of Central New York, but he sub-contracted all except over the most lucrative main stage lines to others. The U.S. Post Office once gave Colonel Sherwood the credit of being the best stage proprietor in the United States so far as prompt deliver of mails was concerned. Sherwood, of Auburn, took great pride in having his stages run on time and always kept good horses.

Interviewed in 1886, Norman Maxon of Elbridge, an oldtime stage driver, told how the horse operated “in the rounds.” He said:

“I began driving in 1828 and the only old drivers known to be living beside myself are, Consider Carter, who lives in Chicago, and George Brown of Danforth. Col. John M. Sherwood controlled that part of the line from Manlius and Fayetteville to Geneva. It was divided into three sections. Eastward from Auburn one line ran through Skaneateles, Marcellus and Onondaga Hill to Manlius. Another went over the Seneca Turnpike through the villages of Elbridge, Geddes and Syracuse to Fayetteville.

“That part of the road between Auburn and Geneva comprised the third section. It would be impossible now for me to tell you the exact number of teams that were employed on the line, but I think 80 would be near the figures. At that time the stages ran through from Albany, the horses only being changed. The teams and and their drivers were in the rounds, that is, ‘first in, first out.’ For instance, a coach came into Fayetteville. My team had been in the stable longest, I would hitch on and drive it to Syracuse, where another team would take it and go on to Camillus.

“When it came my turn I would follow to Camillus and then in order to Elbridge and lastly to Auburn, where I would turn. On the down trip stops were made at the same changing places until I got to Fayetteville, where Parker and Faxton’s teams met ours. The same method was pursued on the Genesee Turnpike and between Auburn and Geneva. The advantage of such a course was it gave the horses shorter drives and saved passengers the delay which would result in stopping to feed.” Except for the lateral lines, most of the east-west stagecoach business ceased with the coming of the railroads.

New York Spectator

February 15, 1828

_____________

Geneva Courier, January 15, 1879

THE LAST STAGE.

THE RAILROAD AND THE STAGES.

_______

The last Stage leaves Geneva Saturday - A look at the past.

_____

Saturday next, January 18, 1879, will mark an era in the history and progress of Geneva. On that day the last stage will make its last trip - the Geneva and Clyde stage line will after Saturday be a thing of the past. The withdrawal of the stage would not in itself be a very noteworthy occurrence, but the fact that it brings the end of the stage business in Geneva is an interesting one.

There was a time when stages were as plenty and nearly as noisy in Geneva as railroad trains are now; when it was a prominent station on the Albany and Buffalo stage route. Our older citizens well remember the sight and sound of the large, heavily loaded stages, as with cracking whips and blowing horns they rattled through the streets, on their way east and west through the villages and wilds of the then new state.

In the busy season it was no uncommon thing for from three to six stages to pass through Geneva every three hours. All stopped at Hemenway's Hotel, now the Water Cure; driving up to the piazza with a grand flourish, the row of coaches standing in front of the house while passengers and drivers went in for refreshment - solid and liquid.

Geneva was one of the important stations on the stage route, and in 1823 orders were given that the mails between Albany and Buffalo should be opened only at Geneva. The stage business was at its height in 1830. In those days stages were the only means of communication for persons desirous of losing no time. A gentleman of this village, who came here in 1822, by stage, left Northampton, Massachusetts, on Monday, and arrived in Geneva on Friday. On one of his trips west from Albany an attempt was made to rob the stage between Albany and Schenectady, by cutting loose the baggage in the boot behind.

The passengers heard the noise, and turned out in time to save their goods. It was not an uncommon thing for the stage to be robbed. In 1811, as shown by an old copy of the Expositor, printed here then, Geneva was the post3 office for Seneca, Sodus, Romulus, Phelps, Junius, Palmyra, Lyons, Crooked Lake, and many other places. E. White, post, informs his patrons that he will no longer carry papers. In 1808 a "post rider's notice" offers an opportunity for people indebted for newspapers delivered by Elijah Wilder so he could pay for his wheat.

In 1823, a New York paper noted as an example of extraordinary speed that a stage traveled from Utica to Albany, 96 miles, in 9 hours and 10 minutes. The same year Ry's Register records that this village is connected with the outside world by three daily stages for Rochester and Buffalo west, Utica, Albany and Cherry Valley east; to Bath and Angelica twice a week; to Ithaca, Owego and Newburgh, three times weekly; and to Lyons and Sodus once a week.

With the completion of the Central road, which was celebrated with great rejoicing on July 4, 1854, the main line of stages was of course discontinued. As the railroads have increased, the stage traffic has fallen off, till for several years the Clyde stage has been the only one left. The construction of the Geneva and Lyons Railroad now necessitates the abandonment of that route, and the victory of the locomotive over the stage is complete.

___________________

Reading Room for Stage Drivers

New York Spectator

February 15, 1828

_____________

Geneva Courier, January 15, 1879

THE LAST STAGE.

THE RAILROAD AND THE STAGES.

_______

The last Stage leaves Geneva Saturday - A look at the past.

_____

Saturday next, January 18, 1879, will mark an era in the history and progress of Geneva. On that day the last stage will make its last trip - the Geneva and Clyde stage line will after Saturday be a thing of the past. The withdrawal of the stage would not in itself be a very noteworthy occurrence, but the fact that it brings the end of the stage business in Geneva is an interesting one.

There was a time when stages were as plenty and nearly as noisy in Geneva as railroad trains are now; when it was a prominent station on the Albany and Buffalo stage route. Our older citizens well remember the sight and sound of the large, heavily loaded stages, as with cracking whips and blowing horns they rattled through the streets, on their way east and west through the villages and wilds of the then new state.

In the busy season it was no uncommon thing for from three to six stages to pass through Geneva every three hours. All stopped at Hemenway's Hotel, now the Water Cure; driving up to the piazza with a grand flourish, the row of coaches standing in front of the house while passengers and drivers went in for refreshment - solid and liquid.

Geneva was one of the important stations on the stage route, and in 1823 orders were given that the mails between Albany and Buffalo should be opened only at Geneva. The stage business was at its height in 1830. In those days stages were the only means of communication for persons desirous of losing no time. A gentleman of this village, who came here in 1822, by stage, left Northampton, Massachusetts, on Monday, and arrived in Geneva on Friday. On one of his trips west from Albany an attempt was made to rob the stage between Albany and Schenectady, by cutting loose the baggage in the boot behind.

The passengers heard the noise, and turned out in time to save their goods. It was not an uncommon thing for the stage to be robbed. In 1811, as shown by an old copy of the Expositor, printed here then, Geneva was the post3 office for Seneca, Sodus, Romulus, Phelps, Junius, Palmyra, Lyons, Crooked Lake, and many other places. E. White, post, informs his patrons that he will no longer carry papers. In 1808 a "post rider's notice" offers an opportunity for people indebted for newspapers delivered by Elijah Wilder so he could pay for his wheat.

In 1823, a New York paper noted as an example of extraordinary speed that a stage traveled from Utica to Albany, 96 miles, in 9 hours and 10 minutes. The same year Ry's Register records that this village is connected with the outside world by three daily stages for Rochester and Buffalo west, Utica, Albany and Cherry Valley east; to Bath and Angelica twice a week; to Ithaca, Owego and Newburgh, three times weekly; and to Lyons and Sodus once a week.

With the completion of the Central road, which was celebrated with great rejoicing on July 4, 1854, the main line of stages was of course discontinued. As the railroads have increased, the stage traffic has fallen off, till for several years the Clyde stage has been the only one left. The construction of the Geneva and Lyons Railroad now necessitates the abandonment of that route, and the victory of the locomotive over the stage is complete.

___________________

Reading Room for Stage Drivers

(From Book D, Miscellaneous Records, Page 183-4, Ontario County Clerk, Canandaigua, Recorded January 19th, 1839).

Articles of Association

Stage Drivers Library and Reading Room Association

Article 1. We the undersigned Stage Drivers of the Village of Canandaigua hereby form ourselves into a society to be known and distinguished by the appellation of The Canandaigua Stage Drivers Library and Reading-Room Association and bind ourselves individually to pay the sum of 12 1/2 cents per month to the President of Said Association which said monies are to be expended from time to time as said President shall se fit for the purchase of Books, Periodicals, &c. for the benefit of the association.

Article 2. No member of this Association or any other person shall have the privilege of removing any book, periodical or other property of this Association from the room in which said books &c are kept.

Article 3. The officers of this Association shall be a president, vice president and librarian who shall be elected by ballot, on the first day of January in each year.

Article 4. The President shall perform all the duties usually incumbent on that office and in his absence those duties shall be performed by the Vice-President.

Article 5. Any Stage Driver in Canandaigua may become a member of this Association by subscribing this constitution and complying with the requirements herein contained.

Article 6. This constitution may be amended by vote of two-thirds of the members of the Association.

Canandaigua, January 1st, 1839.

President Stephen B. Austin

Vice President George B. Hotchkiss

Librarian Perry G. Wadhams &c.

______________

A typical stagecoach of the 1820-40 period called the "Troy Coach." This one was owned by Thorpe & Sprague of Albany. From: "Forty Etchings, From Sketches Made With The Camera Lucida, in North America, in 1827 and 28" By Captain Basil Hall. (Cadell & Co., Edinburgh, 1829)

______________

A typical stagecoach of the 1820-40 period called the "Troy Coach." This one was owned by Thorpe & Sprague of Albany. From: "Forty Etchings, From Sketches Made With The Camera Lucida, in North America, in 1827 and 28" By Captain Basil Hall. (Cadell & Co., Edinburgh, 1829)

Geneva Gazette

Feb. 16, 1825

(Advertisement)

Three times a Week

From Geneva to Penn-Yan

Leaves Geneva Mondays, Thursdays & Saturdays.

Leaves Penn-Yan Tuesdays, Fridays & Sundays.

____

MAIL STAGES have commenced and will run regularly twice a week from Owego, by the way of Tioga Point, Chemung, Elmira, Big Flats, Painted Post, Campbelltown, Bath, Howard, Hornellsville, Dansville, Geneseo and Avon, to Rochester. Also, to Olean Point by way of Bath and Angelica - through in less than 3 days - Fare, $6.25. Leaves Owego and Rochester on Wednesdays and Sundays, - From Geneva by Penn Yan, Wayne, Bath, Howard, Hornellsville, Almond, Angelica, Friendship, Oil Creek, to Olean Point - through in 2 1/2 days - Fare, $5.00. Leaves Geneva Mondays and Thursdays; Olean, Wednesdays and Sundays.

These lines meet regularly at Bath and Hornellsville, so that travellers may pass to either section without delay. They intersect, at Geneva and Avon, the Albany and Buffalo lines; at Rochester, the Lewiston line; at Geneseo, the Canandaigua & Moscow line; at Painted Post, a line to Williamsport, Pa.; at Elmira, a line to the latter pace - also, a line from Berwick, Pa. to Geneva, by way of Ovid; at Tioga Point, a line to Wilkesbarre; at Owego, the several lines from New York, Milford, Newburgh and Ithaca, Washington City, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Lancaster, Easton, Harrisburg, Northumberland, Wilkesbarre, Montrose, &c.

Good Horses, new Coaches, and careful, attentive Drivers are employed. Every attention will be paid to the comfort and safety of Passengers. The Proprietors have expended large sums in establishing these lines, and are determined to conduct them at all times in such manner as to merit a liberal patronage.

JOHN MAGEE, of Bath,

and Others, Proprietors.

January 1, 1825.

N.B. - Boats and Skiffs of all sizes will be constantly kept at Olean to accommodate such as may wish to descend the Allegany river, during the months of April, May, June, July, October, November and the fore part of December. Travellers may generally pass from Geneva to Pittsburgh in about 5 or 6 days. When there are two or more in company, their whole expenses will not exceed ten dollars each.

Note: John Magee was a pioneer stagecoach proprietor in the Southern Tier.

_____________

Perry Democrat, Aug. 12, 1841

STAND AWAY CANOES,

And let the Steamboat Come

THE Subscriber has commenced running a Line

of Mail Coaches from

ALEXANDER to GENESEO,

Leave Geneva every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, at three P.M. - arrive at Alexander at 11 P.M., intersecting the Swiftsure line of Stages to Buffalo and Batavia.

Leave Alexander every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, at 5 o'clock A.M. - arrive at Covington at 9 1-2 A.M., and Geneseo at 12 M., intersecting the Canandaigua, Dansville, Mount Morris and Rochester States, and the packets on the Genesee Valley Canal, passing through the following places: Attica, Vermal, Lindon, Middlebury, Pearl Creek, Covington, Peoria, Pifferdinia, to Geneseo.

Passengers will find it to their advantage to take this Stage, as this is the shortest and most direct route from Canandaigua to Buffalo, and passage through a delightful country.

Good Horses and Carriages, and none but careful Drivers employed.

J.D. BARTLETT.

Alexander, July, 1841