(From: History of Cherry Valley by John Sawyer [Cherry Valley], Page 81, 1898)

In 1815 Cherry Valley had reached its greatest relative importance. It continued to grow in wealth and size, but its growth, in the latter respect especially, was slow and it was soon left behind by the rapidly growing villages of Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo and many others.

The great ability and reputation of its many citizens continued to give it, for many years, a prominence far greater than the many places greatly exceeding it in population. The rapid growth of the country to the west also added to the business and wealth of the place, as the greater part of the travel, to and from that section, passed through it. How great this traffic was, is shown in the fact that, at this time, there 62 taverns between Albany and Cherry Valley, - a distance of 52 miles.

That this place must have benefitted enormously from, and had been a great center for, this trade, is clearly indicated by the fact that there were fifteen taverns and ten retail liquor stores in the town. In addition to these there were four distilleries - on the present Thomas Wikoff (P. 82) farm, at Flint's, on East Hill, and art Salt Springville, - and one brewery on the Wikoff farm.

There were eight blacksmith shops, giving employment to from four to eight men each, and at one time 110 stage horses were kept in the village. In addition to the through stage lines from Albany and New England States to Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo and the West, local stage lines connected Cherry Valley with Albany, Schenectady, Catskill, Canajoharie, Burlington, Monticello, the Worcester towns, Cooperstown and Utica.

Stages were usually drawn by six horses, though eight, even ten, horses were used at times. Regular freight transportation lines were also run between Albany and Buffalo. Huge wagons capable of drawing from three to four tons, drawn by seven horses, were used on these lines. They moved slowly, the journey from Albany to Buffalo often taking two weeks.

These wagons had tires six inches wide and were allowed to pass through the numerous tollgates free of charge, owing to the fact that their wide treads were of great benefit to the roads by filling in the runts made by ordinary wagons. This enormous traffic caused a great demand for horses and the price of those animals, which had been from twenty-five to thirty dollars, in 1800, had risen to from $75 to $150 by 1820. Much above the price which ordinary horses now command in this section.

____

The Town of Winfield By Byron A. McKee, Papers Read Before the Herkimer County Historical Society, Vol. 3, P. 47, Herkimer, 1914. (McKee's paper read March 14, 1903).

When the Cherry Valley and Manlius turnpike was laid our it traversed the more central part of the town, and thereafter the tendency of the population was to locate upon or near the turnpike. It was also called the Third Great Western Turnpike, the First Great Western leading from Albany being north of the Mohawk; the second being south of or near the Mohawk and the third being generally located on the high land south.

In my recollection, the turnpike was much used, great loads of all kinds of produce being being drawn over it to Albany, and goods for merchants in the interior being drawn back. It was customary for teamsters to carry their own provisions and provender for their teams. The charges for such, at the taverns being very moderate, not more than one shilling and six pence for lodging and hay. Great droves of all kinds of animals, required for the city, cattle, sheep, swine and even turkeys were frequently to be seen.

Turkeys in large flocks were not bad to drive, except that in the after part of the day, if they neared an orchard, the turkeys were apt to take to the trees and no one could stop them; their day's march was ended. However, they were early to start in the morning and probably accomplished a fair day's journey in the day.

The Third Great Western Turnpike, leading out of Albany, was laid out for rods wide, and six rods wide through the villages. This was necessary from the frequent droves and the large amount of travel. The road was "worked" the full width, that it all might be used.

One of the most interesting and exciting sights in those days was the passage of the great four horse stages, usually loaded with passengers and at full speed. Then, as now, the roads in that part of the town were good, being well gravelled and not very hilly; and it was the custom to 'make up' time, on the good roads in that section, loaded inside and out with its four or six horses coming down the road at a full gallop, a sight well worth seeing at the present day.

Then the drivers would pull up at the post-office with a flourish and within a few inches of where they intended. I spell Driver with a capital D, for to us they were as much heroes as is the engineer of a fast train. Many and interesting exploits, and the safety of their valuable cargo was always uppermost with them, an d they had to make time if possible, in all kinds of weather and all conditions of the roads.

Time was valuable then as now, and when the old Pioneer Line of Stages from Albany to Buffalo, "through in six days," had made that time for some years, a new line established, the Telegraph Line, "through in four days," and "passing the principal points of interest in daylight," just as the Twentieth Century Limited now advertises the time from New York to Chicago reduced to twenty-four hours.

(P. 51) Before the turnpike was abandoned, it was well cared for, being divided into divisions as railroads are divided in sections, each division being in charge of a superintendent, and he generally performed his duty faithfully and well. Two men and two horses and a cart, plough and scraper and necessary tools were kept on the road all the time, going over the division, from one end to the other, and doing such work as was best for the maintenance of road and keep it in good condition at all times. After the building of the Utica and Schenectady Railroad some travel was diverted to the Mohawk Valley, but not enough to make any appreciable difference in the travel over the turnpike.

____

Otsego Farmer, Cooperstown

October 2, 1914

A THOROUGHFARE OF THE PAST

_______

The guide on the "Seeing Boston" car points out "the longest street in New England." New York State has one that is of equal interest. As the suburbanite drives out Western avenue, Albany, he finds himself on a street that leads to Buffalo, known sometimes as the Western Turnpike, and to others as the Cherry Valley Turnpike, and still elsewhere as Genesee Street.

About fifteen miles from Albany, after many low hills have been ascended, and innumerable streams crossed, the road mergers with the old State road. This was built in 1812, from West Albany to the fort at Oswego. The soldiers, making a path through the wilderness, felled trees, and made a road-bed of the trunks. Until a few years ago, these old "corduroys" occasionally worked to the surface during the spring upheavals.

More than half a century ago, this Western Turnpike was the great thoroughfare toward the west. In those days people spoke of a trip to Onondaga or Genesee country as going "out West," for Chicago was still a stretch of uninhabitable land; and the region beyond the Mississippi was the vast unknown.

So it was that emigrant wagons took this route to their new homes beyond the borders of the state. Throngs of men, women and children, too poor or too thrifty to pay the price of passage by the Erie Canal, tramped their way, with bundles slung on their backs, toward the land of promise. A few paid, in money or work, for their meals at the farmers' houses, but most of them begged of the hospitable people, who were ashamed to turn away even one hungry one. Many found a weeks' work among the farmers and stopped to earn a little before continuing the westward way.

But the travel was not all to the west. Many people had settled in the rich valleys of southern New York, or on the hills of Schoharie and Delaware counties. There as no market nearer than Albany. So as summer ripened into autumn, the farmers began their trips down the Turnpike, with droves of cattle, sheep, and hogs. Along the road were numerous taverns, especially in a day's journey of Albany.

Here the drovers stopped for the night, and sat telling yarns and comparing notes in the big hall, while their cattle fed in some farmer's field. If the grass had all been eaten by the early comers the farmers brought hay from his barns. Occasionally a flock of turkeys, a sore vexation to the driver, came down the pike, roosting on convenient fences at nightfall.

Sometimes the children were awakened at night by the voice of some rough stranger, who, finding the taverns full, had sought shelter with a farmer. Perhaps he found lodging by the kitchen fire, but oftener on the hay in the barn loft.

Later in the season, as the snow-flakes began to fly, great wagons rattled over the frozen ground, ladened with meat and poultry for the holidays. Twelve miles from Albany, one December day, from day-light till dark, one man counted eleven hundred sleighs loaded with pork. Many drivers stopped for the last night ten or fifteen miles from the city, returning to spend the next on the homeward way, but others traveled the whole night through.

Sometimes a wife or daughter, afraid to trust a masculine shopper, had without the resources of her grand-daughter by mail and express, braved the long, cold ride for a glimpse of city "stores," and the latest styles.

At the time when rural boarding schools flourished, dozens of these sprang up in the valleys of interior districts. Not only the sons and daughters of the sturdy farmers, but many from the eastern part of the sate, flocked to them in great numbers. The academy at Charlotteville housed at one time nine hundred students. There were no railroads by which these schools could be reached, so the students, the furniture, the pianos, and all such provisions as tea, sugar, and even flour, must be carried by wagons and sleighs from Albany, at enormous expense.

Four-horse teams struggled over the hills with provisions for the small villages. That the condition of the roads was such as to make travel a struggle is attested to the fact that the great-grandfather of the writer many times rose from his bed, took rails from his fences, and helped pry loaded wagons from the mud. It was said in those days that the road was so straight the wind blew through it as through a tunnel, making it bitterly cold.

As time passed, Sharon Springs and Richfield Springs became noted as summer resorts. Then, in the early summer, the residents along the Turnpike saw fine carriages and livered footmen pass, and said, "There goes someone to the Springs." These gay people, too, were dependent on the humble fare of the taverns for their meals.

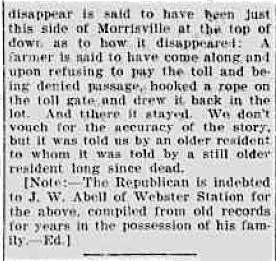

At one time, half the road was was planked for eleven miles out of Albany, to make travel easier, and numerous toll-gates were erected for the collection of rates. About sixty years ago, a gate-keeper two miles from Albany took toll, within twenty-four consecutive hours, for 2,700 teams on their way to the city.

Here and there one sees farmhouses that were once taverns, little changed inside or out. But the successor of the farmer who once drove his cattle to Albany, owns stock in a cooperative creamery, or sends his milk to New York, by way of a railway built for him and his neighbors. His eggs and poultry go by express to New York or Philadelphia. The telephone and the rural mail carrier keep him in touch with the outside world, his provisions are often brought to the door by a grocery wagon, and his family shop in New York or Chicago. The old Turnpike, so great a boom in days gone by, is well-nigh deserted.

______

Syracuse Post-Standard

July 9, 1917

Madison County Times, Morrisville

June 19, 1925

______

Richfield Springs Mercury

Thursday, December 22, 1966

No comments:

Post a Comment